THE STORY BEHIND: Prokofiev's Symphony No.5

Share

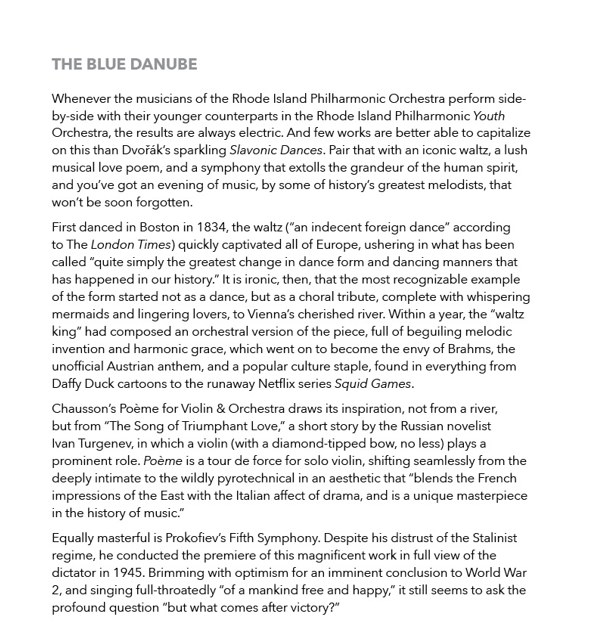

On January 24, Music Director Ruth Reinhardt and the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra will present THE BLUE DANUBE with violinist Charles Dimmick.

Title: Symphony No.5 in B-flat major, op.100

Composer: Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic: Last performed September 20, 2014 with Larry Rachleff conducting. This piece is scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano and strings.

The Story: From the time Sergei Prokofiev left Russia after the 1917 revolution to well into the 1930s, the highly prolific composer had created dozens of popular works for stage and for chamber and orchestral ensembles. His music had found acceptance far beyond Russia’s borders, and he was in great demand as a performer and conductor throughout Europe and the United States. Hoping to bolster its cultural standing in the world, the newly formed USSR encouraged Prokofiev to return to his homeland, promising greater opportunities for him and his fellow musicians. Cautiously optimistic, Prokofiev agreed, and while initially things seemed promising, the rise of Stalin meant that artists of all sorts were soon subjected to extreme oversight, sent away to work camps, executed, or simply disappeared. Prokofiev himself was never again allowed to leave Russia, and he tread with great care when considering what to compose and how to present it.

In a rare act of generosity, Stalin invited Prokofiev and his colleagues Glière, Shostakovich, Khachaturian, and Kabalevsky to spend the summer of 1944 at a retreat in Ivanovo, about 150 miles outside of Moscow, so they could compose in an environment free of city bombings and wartime shortages. It was there that Prokofiev penned the first draft of his fifth symphony. In language that sounds like an attempt to appease the censors, Prokofiev described it as “glorifying the human spirit. I wanted to sing of a mankind free and happy - his strength, his generosity, and the purity of his soul. I cannot say that I chose this theme. It was innate in me and had to be expressed.” His PR strategy worked, and even enjoyed a serendipitous boost when, while conducting the work’s 1945 premiere in Moscow Conservatory’s Great Hall, the composer had to pause before his first downbeat, as he was interrupted by celebratory gunfire signaling the victorious advance of the Red Army across the Vistula River into German territory.

Rather than opening in a customarily fast tempo, Prokofiev’s fifth symphony begins with a noble Andante.

This allows Prokofiev to infuse the music with some of his most colorful writing, especially for the wind and brass sections. Listen for the elegant lyricism shared by flute and bassoon in the relatively calm first theme, and for tremolo strings that propel an elaborate development towards an electrifying coda. We also hear plenty of his trademark harmonic “side-slips” that frequently take the music – seemingly inevitably - into wildly unexpected places.

The second movement is a scherzo (the musical term for “joke”) in all but name. Adding to his already rich orchestral color palette, Prokofiev calls upon percussion and trumpet to lead us on an exhilarating ride, while clarinets dazzle us with virtuosity. Folksy tunes with ever-shifting rhythm patterns, played mostly by oboe and clarinet, provide an exotic respite in the middle section, followed by a breathless

accelerando

that leads us back to the movement’s opening material.

The dreamy

Adagio

movement forms the center of gravity for the entire symphony. A haunting ambiguity pervades this movement, wafting somewhere in between major and minor modalities. Above this uncertainty, one of Prokofiev’s most beautiful melodies soars in the violins. Also of note is a refrain of special poignancy, always played by the oboe and bassoon, that eventually builds to a tortured climax before receding to a quiet end.

The finale begins in almost whimsical fashion, with a cello choir playing a slow introduction that recalls the first theme of the first movement. The violas then usher in a new mood, inviting the high-spirited clarinet to give us another dazzling display of virtuosity. Then, just as the movement is striving to end on a victorious note, the music degenerates into a frenzy, which is stripped down to a string quartet playing staccato "wrong notes" with rude interjections from low trumpets. Color and irony dance in unbridled splendor here, making for a wild and brilliant conclusion to what is arguably the greatest symphonic masterpiece of the mid-20th

century.

Program Notes by Jamie Allen © 2025 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Recommended Recordings:

Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra cultivated their own sonic patina. That special luster, when applied to Prokofiev's Fifth Symphony (1957 on Sony), delivered one of the work's finest recordings. Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic (1968 on Deutsche Grammophon), with their astonishing virtuosic polish, also deliver a thrilling account.

Tickets start at $25! Click HERE or call 401-248-7000 to purchase today!