THE STORY BEHIND: Jaëll's Cello Concerto

Share

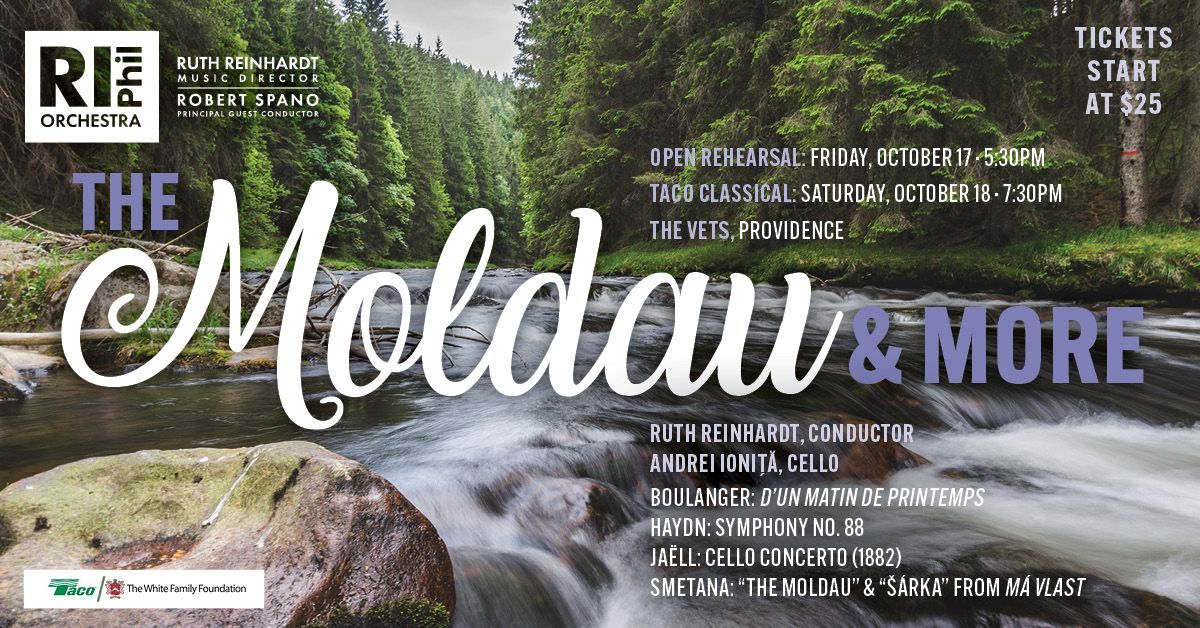

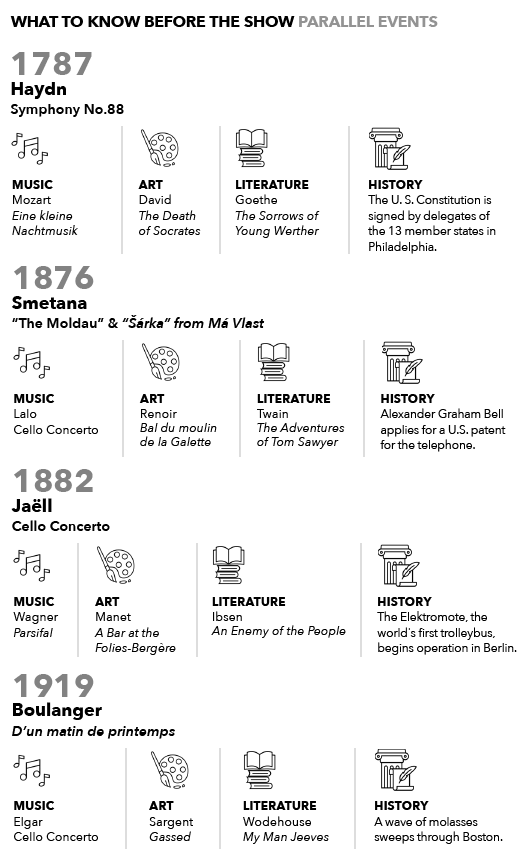

On October 18, Music Director Ruth Reinhardt and the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra will present THE MOLDAU & MORE with cellist Andrei Ioniță.

Title: Cello Concerto, F major

Composer: Marie Jaëll (1846-1925)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic:

This is a RI Philharmonic Orchestra premiere. In addition to a solo cello, this piece is scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani and strings.

The Story: The only real way to judge a piece of music is by listening to it. Although music lovers with an interest in out-of-print scores may have been able to get hold of some of Marie Jaëll’s piano music, her orchestral music has not been heard since its first performance. Her major orchestral works provide an unexpected study of a composer whose instrument of choice might not have been, as was commonly believed, the piano – on which the virtuoso excelled in her first period of activity from 1855 to 1870 – but that ‘king of instruments, the orchestra. Indeed, she had every right to be proud of her experiments in orchestration, her sense of drama, her subtle instrumentation and at times truly Impressionist textures.

“How insipid they are, these young women pianists who always play the same pieces by Liszt. But speak to me of La Jaëll! Here is an intelligent, witty woman: she produces her own works for the piano, which are just as bad as those by Liszt.” It is hard to know how to take this strange tribute paid by Johannes Brahms to ‘La Jaëll’ in a letter of 1888 to Richard Heuberger, when he compared her compositions ironically – or cruelly – to those by Liszt. Brahms was a longstanding friend of the virtuoso pianist, Alfred Jaëll, who first performed and promoted many of the German master’s works, so he would have known Marie Trautmann, who became Marie Jaëll in 1866. But whether Brahms was really familiar with the Alsatian prodigy’s music is another matter. Were her pieces so widely distributed, played in the salons, published, discussed and reviewed in her day that it was amusing to ridicule them by comparing them disparagingly to works composed by that obscure pianist, Franz Liszt? There may well be parallels, on a different scale, between Liszt and the woman who later became his confidante and secretary: Liszt’s talents as a composer seem to have gone unrecognized, and were even derided, for many years, unlike his genius as a pianist and improviser, a performer whose keyboard feats won him standing ovations throughout Europe. Was Brahms, in this letter, espousing a similar prejudice against virtuosi impudent enough to aspire to the noble art of composition? Whatever the case, it is difficult not to find him guilty of the widely shared misogyny which Marie Jaëll, along with other creatively active women, would have had to endure to some extent or other.

Marie Jaëll’s body of works, however, although not prolific, does shed some light on the interest her music might have aroused at the time she was writing it, as well as on the unusual artistic path taken by a young piano prodigy who decided, in her twenties, to turn her back on an established career as a renowned performer. These works also show glimpses of the complicated concerns and enquiries of a certain Romantic strain of French music in the second half of the 19th century, a period influenced equally by a strong Italian heritage, a fascination for German and Austro-Hungarian models and a quest for a unique French identity. In 1878, she confided to her friend, Anna Sandherr: “Learning to compose is an abiding passion, I wake up with it in the morning, I go to sleep with it in the evening. I have such an elevated idea of my art that my only delight is to devote my life to it without hoping for anything else but to live through it and for it.”

The Cello Concerto in F major (1882) was also highly successful, since its dedicatee, the famous cellist, Jules Delsart, worked hard to promote it. The Belgian cellist, Adolphe Fischer, another renowned performer and the dedicatee of Lalo’s Cello Concerto, seems to have asked Jaëll for permission to perform the work at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. Unlike certain other concertos in which the soloist tends to get swallowed up by the orchestral texturing (Dvořák’s masterpiece, for example, composed in 1896), the subtle scoring of Jaëll’s Cello Concerto shows a close attention to the material and a light touch which brings out the melodic line of the cello. It might also be worth noting that these two concertos – by Dvořák and Jaëll – share a surprisingly similarity (particularly in their respective first movements) in that they both have a resolutely ‘American’ inspiration: Marie Jaëll’s sister was the first wife of Conrad Diehl, a German doctor later elected mayor of the city of Buffalo. The Alsatian composer was very fond of her American nieces and nephews, whom she made her legatees after her death. After a spirited Allegro moderato, which transports the listener into the midst of vast unexplored spaces, the composer hits a particularly rich vein of inspiration in the slow movement, a delicate Andantino sostenuto in the strings, alternating pizzicati and bowed notes each time the melody recurs; the short central section of the movement, with its unusual 9/16 time signature – a sort of triple beat within what is already a triple beat – emphasizes the poignant push and pull of the expressive musical writing, and greatly enhances the impact of the floating cello line. The impassioned tarantella-style finale concludes this extremely condensed work, barely fifteen minutes long, which is attractive for its simplicity, energy and brilliance. The restricted instrumental forces invite the cello to take center stage in the musical discourse, surrounding and arraying the soloist with carefully worked colors and textures.

A career woman and artist who had earned her place in a male-dominated world, Marie Jaëll strove to gain recognition from her peers and become, in a manner of speaking, the Frenchest of French composers. She actively opted for France after Alsace-Lorraine was annexed and chose to study under Camille Saint-Saëns, a true national treasure. In 1879, she was the first woman to be admitted to the Société Nationale de Compositeurs de Musique; her works were frequently performed at concerts organized by the Société Nationale de Musique.

But how should her sometimes enigmatic musical output be categorized? Was she a typically French composer? A composer of German inspiration? Although Marie Jaëll protested throughout her life against a Wagnerism she was reluctant to acknowledge, it should be remembered, nevertheless, that her early piano training was dominated by the German and Austrian repertory, which left its indelible stamp on her work; later, her extensive acquaintance with Liszt’s works, as well as the series of sensational concerts during which she performed not only the complete Beethoven sonatas, but also Chopin’s complete piano music, only strengthened the impression that this woman, in her heart and soul, looked to Germany, and beyond.

However, in the midst of this unresolvable conflict of loyalties, she attempted to go her own way and we can identify several hallmarks of her idiosyncratic approach: her emphasis on colorful, imagistic writing and an exploration of the natural and inner worlds; her fusion of all the instruments together – soloists or not – so that their complex individual lines work together to create a unique discourse, a single orchestral voice; her realization of a type of minimalism in which the initial material is not varied, developed and enriched in the classical style, but remains unembellished to the end. Focusing on an unexpected instrument, the orchestra, she produced groundbreaking work, becoming a pioneer on her own terms. She invented a free art of orchestration in which the material was governed, shaped and crafted entirely by the poetic aim.

Sébastien Troester

Reproduced in edited form by permission.

From the BruZane release Marie Jaëll: A Portrait available HERE and available through Amazon.

Recommended Recordings:

Marie Jaëll Cello Concerto only recently received its first and only recording on the Bru Zane label, a set of three discs of her music.

Tickets start at $25! Click HERE or call 401-248-7000 to purchase today!