THE STORY BEHIND: Verdi Requiem

Share

On May 5 & 6, conductor Tania Miller and the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra will present VERDI REQUIEM with Providence Singers, Christine Noel, Artistic Director, and soloists Laquita Mitchell, soprano, Susan Platts, mezzo-soprano, David Pomeroy, tenor and Kevin Deas, bass.

THE STORY BEHIND: Verdi Requiem

Title: Requiem

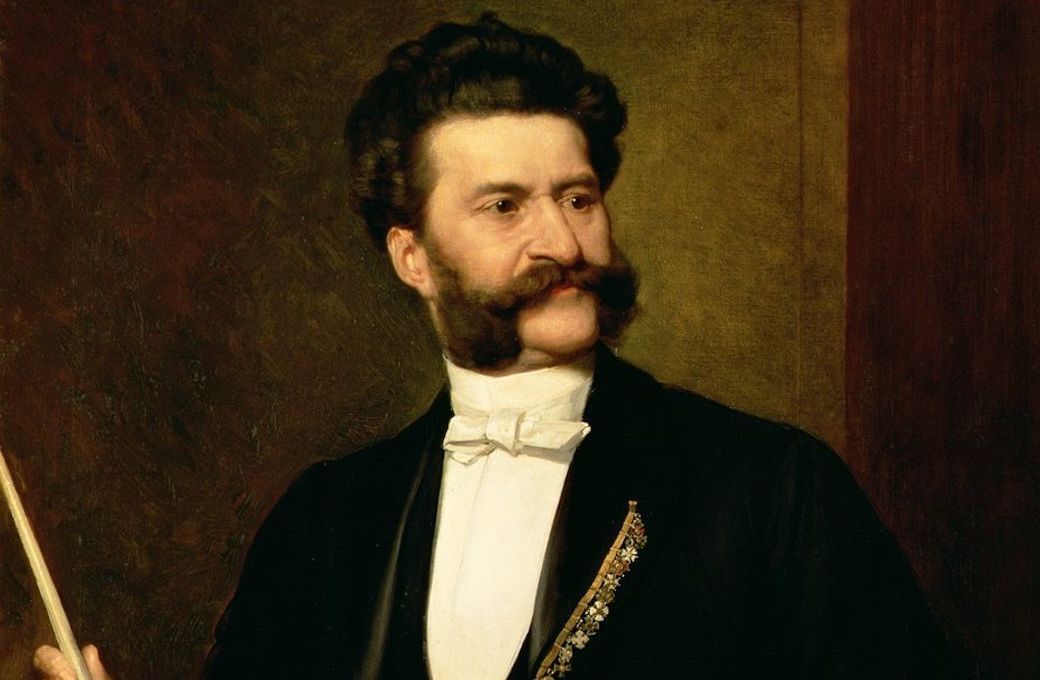

Composer: Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic:

This is a RI Philharmonic Orchestra premiere. In addition to a chorus, a solo soprano, alto, tenor and bass, this piece is scored for two flutes, piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, four bassoons, four horns, eight trumpets, three trombones, ophicleide, timpani, percussion and strings.

The Story: When opera composer Gioachino Rossini died in November 1868, Giuseppe Verdi conceived a grand project to commemorate the anniversary of his death. It was to be a

Requiem

Mass for which the most prominent Italian composers of the time would each contribute one movement. Verdi reserved for himself the last movement, the

Libera me, not officially part of the Requiem but sometimes appended to it. The Mass was to be celebrated in the Cathedral of San Petronio in Bologna, where Rossini had grown up. Unfortunately, Verdi’s plan fell through due to lack of cooperation by municipal officials and the impresario of the Bologna Opera. Verdi had already sketched his Libera me, but he had to put it aside for a time, as the composition of

Aida occupied his efforts for the next few years.

Then, in May of 1873, another giant in the arts of Italy passed away. This was the novelist-poet, Alessandro Manzoni, whose book,

I Promessi sposi

(The Betrothed), had held Verdi in such awe that in 1867 he had written, “In my opinion, he has written a book that is not only the greatest product of our times, but also one of the finest in all ages that has come from the human mind.” To Verdi, Manzoni was not only the Shakespeare of Italian literature but also a great patriot. For nearly 30 years, Italy had fought to rid itself of foreign occupation and unite its various provinces under a single government. Manzoni had passionately supported this

rinascimento

effort in his writings, as had Verdi through the patriotic elements in his early operas. In 1870, the re-unification of Italy had become a reality, and Manzoni could die with that knowledge and with the undying gratitude of his nation, including Verdi’s personal debt of gratitude.

That debt was paid when Verdi revived his idea of a Requiem in 1873. He had felt the loss of Manzoni deeply. Rather than braving the mobs that thronged the funeral, Verdi had visited Manzoni’s grave alone a week later. Almost immediately, he proposed a Requiem Mass for the first anniversary of Manzoni’s passing. This time, however, it would be completely his own work and would be premiered in Milan, Manzoni’s home and resting place. The city was enthusiastic, and plans went forward.

With the

Libera me already in place, Verdi composed the rest of the Requiem in Paris between summer 1873 and spring 1874. The composer conducted its premiere on May 22, 1874, the exact anniversary of Manzoni’s death, in the Church of San Marco, Milan, chosen for its size and acoustics. The event was a resounding success, and the Requiem was repeated three times in the next several days, but this time at La Scala. Soon there followed a “Requiem tour” in which Verdi conducted the work in Paris, London, and Vienna.

Perhaps it was La Scala’s atmosphere that raised some questions in the press and elsewhere about the Requiem. Certain portions, notably the Dies irae, contain operatic gestures. Some reviewers rebelled against such music in a religious context, calling it “tawdry,” “cheap,” “sensational,” “unreligious,” and “melodramatic.” The conductor, Hans von Bülow, without even hearing the music or seeing a score, climbed on the bandwagon and wrote a scathing, offensive “review.” However, after Brahms had taken him to task for his blunder, the conductor wrote a fawning apology to Verdi. The composer took it all in stride, for words of criticism never seemed to faze him.

Yet such responses might make us curious. What was Verdi’s personal religion? Was he a believer? Years before, Verdi’s wife had written to a friend, “. . . this

rascal

claims, with a calm obstinacy that infuriates me, to be not an outright atheist but a very doubtful believer.” From such words, it is easy to see why Verdi’s Requiem is so different from earlier settings, notably by Mozart, Cherubini, and Berlioz. Nevertheless, Verdi’s wife defended his work, placing the musical style of the Requiem in perfect perspective:

I say that a man like Verdi must write like Verdi, that is, according to his own way of feeling and interpreting his text. The religious spirit and the way in which it is given expression must bear the stamp of its period and its author’s personality. I would deny the authorship of a Mass by Verdi that was modeled on the manner of A, B, or C.

The opening part, “Requiem aeternam,” gives no hint of music that would elicit some critics’ sarcastic remark that the Requiem was Verdi’s “greatest opera.” Instead, a purely liturgical mood prevails, and with it the traditionally liturgical devices of smooth, conjunct lines and well-crafted counterpoint. A passage for the chorus a cappella even nods in the direction of Palestrina. With the “Kyrie” comes the introduction of the soloists’ quartet, and the chorus’s ingress completely fulfills the movement’s promise of solemn religiosity.

The second part of the Requiem, the “Dies irae,” is the work’s center of gravity. The text is a lengthy, metrically rhymed

sequentia, Thomas of Celano’s 13th-century vision of the Last Judgment. It virtually cries out for dramatic treatment. Verdi answers that call by creating an “act” of music divided into sections that resemble “scenes.” The impact of the first “scene,” the choral “Dies irae,” suggests the wailing of lost souls on doomsday (in a musical style foreshadowing the storm scene that opens

Otello).

Likewise theatrically conceived is the fanfare of the “Tuba mirum” between on-stage and off-stage trumpets. Its power continues in the choral-orchestral declamation that suddenly halts as the bass soloist reflects on “Mors stupebit.” This turns out to be an introduction to the mezzo-soprano’s lengthy soliloquy (“Liber scriptus”) in which the chorus keeps murmuring “Dies irae” and finally explodes into an abbreviated reprise of the opening music. Unruffled, the mezzo-soprano continues (“Quid sum miser”), joined at last by soprano and tenor soloists for a Verdian ensemble.

“Rex tremendae” is a big, grand opera-like “scene” involving all soloists, chorus, and orchestra. This leads to the “Recordare,” beginning as an intimate duet for soprano and mezzo-soprano. Now it is the male soloists’ turn for soliloquy: first the tenor, “Ingemisco tamquam reus,” and then the bass’s more agitated “Confutatis maledictis.”

The bass soloist’s final cadence collides with a restatement of the “Dies irae” opening chorus, turning now to another key for the conclusion, “Lacrymosa.” In this pious lament, Verdi gradually returns to the liturgical expression of the “Kyrie,” ending this moving yet controversial “act” with an unexpected harmonic shift at the “Amen.”

The “Offertorium” part of the Requiem belongs to the soloists. Liturgical in feeling and deeply sincere, it nonetheless invites Verdi to employ a few effective gestures associated with opera. One is the entrance of the soprano on a long, floating high note (“Sed signifer Sanctus Michael”) as angelic as St. Michael himself. Another is the string

tremolo

that provides a shimmering effect with the tenor’s beautiful “Hostias.” The words “Quam olim Abrahae promisisti et semini ejus” traditionally had been set as a fugue. Verdi writes contrapuntally, but not as a formal fugue, since his conception of the text is essentially lyrical. To round out the movement, “Libera animas” restores the gently rocking rhythms of the opening.

In the relatively brief “Sanctus,” Verdi finally displays his profound contrapuntal skill through a double fugue for split chorus and orchestra. Rather than separating the “Hosanna” and “Benedictus,” as traditionally was done, this movement treats the words as one continuing sentence, although the final “Hosanna” is in a texture that contrasts with the movement’s prior polyphony.

Beginning in octaves and in an

a cappella manner reminiscent of Gregorian chant, the soprano and mezzo-soprano soloists plainly introduce the theme of the “Agnus Dei.” The movement proceeds almost as a set of variations on this devotional lyrical melody, alternating soloists with choral responses until the threefold invocation is complete.

The Communion, “Lux aeterna,” with which a Requiem Mass normally ends, is here set in a mood of somber mystery. However, since Verdi wishes to reserve the literal reprise of his “Requiem in aeternam” for the final movement, he finds a new and more personal expression for these words, set aptly for soloists.

With the opening recitatives of the “Libera me,” we are plunged again into the human-divine drama of the “Dies irae.” Soon, in fact, comes a literal recapitulation of that movement’s astonishing beginning. This turns in a new direction with the reprise of “Requiem aeternam,” now exquisitely enhanced to include the soprano soloist over the chorus. Suddenly, the soloist reminds us of the human condition by bringing back the “Libera me.” This time it leads to a choral-orchestral fugue (with soprano commentaries), humanistic to an extreme, yet offering the deeply spiritual hope of eventual triumph over death.

Program Notes by Dr. Michael Fink © 2023 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Tickets start at $15! Click HERE or call 401-248-7000 to purchase today!