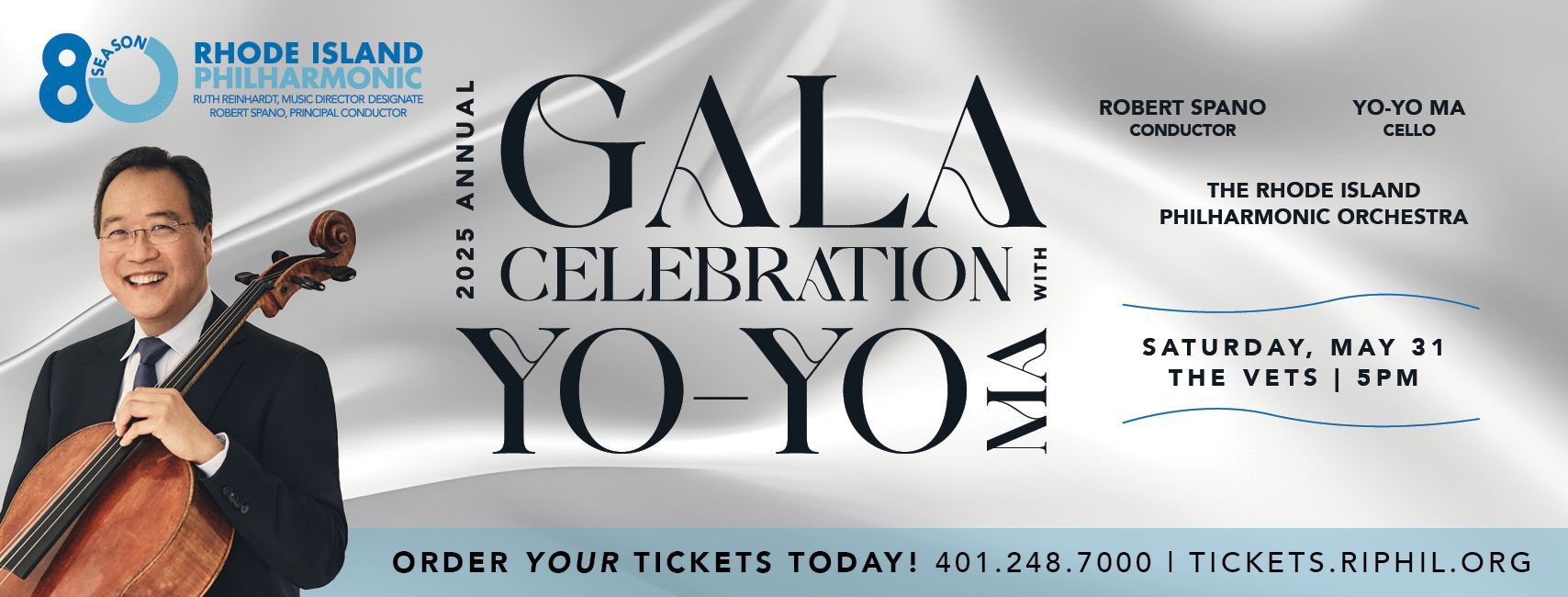

THE STORY BEHIND: The 2025 Annual Gala Concert with Yo-Yo Ma

Share

On May 31, conductor Robert Spano, cellist Yo-Yo Ma and the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra will present the 2025 ANNUAL GALA CONCERT WITH YO-YO MA.

Title: Rainbow Body

Composer: Christopher Theofanidis (1967- )

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic: This is a RI Philharmonic Orchestra premiere. This piece is scored for piccolo, three flutes, three oboes, three clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, three bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano and strings.

Title: Appalachian Spring: Suite

Composer: Aaron Copland (1900-1990)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic: Last performed February 15, 2020, with Alexander Mickelthwate conducting. This piece is scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, percussion, harp, piano and strings.

Title: Cello Concerto, op.104, B.191, B minor

Composer: Antonin Dvořăk (1841-1904)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic:

Last performed September 27, 2008, with Larry Rachleff conducting and soloist Alban Gerhardt. This piece is scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, three horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion and strings.

A Rich and Varied Tapestry of American Music

Rhode Island Philharmonic Principal Conductor Robert Spano has described the first two pieces on this Gala Concert program as “A rich metaphor for the varied tapestry of American music,” but this description could easily be broadened to include the third piece. As surprising as it may sound, Dvořák’s Cello Concerto has bona fide American roots as well.

Spano has long been a champion of the work of the American composer Christopher Theofanidis. After conducting the premiere of

Rainbow Body with the Houston Symphony in 2000, Spano went on to make a celebrated recording of the piece on the Telarc label with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra in 2003. Spano uses both that recording and this Gala program as an opportunity to frame the younger work in a rich and meaningful context by pairing it with Copland’s iconic

Appalachian Spring: Suite.

Theofanidis himself is a firm advocate of this kind of pairing: “It helps you hear both repertories with a certain kind of open ear and freshness,” he says. “They really help each other. It’s not just a one-way thing where new music benefits from being paired with the old. It really goes both ways.”

The sound world created by Aaron Copland in

Appalachian Spring: Suite (and the original ballet from which it was adapted), is one of panoramic landscapes, fertile fields and broad prairies. It has, in fact, become a sound symbol of America itself. Its spacious harmonies, delicate suspensions and inescapable tunefulness never cease to resonate with audiences. And while the ballet tells the story of a young couple living on a farm in rural Pennsylvania in the early 1800s, the orchestral suite transcends any specific plotline, invoking a shimmering spirit of hope for an unknowable future. Looking at their vastly different sources of inspiration, it may then seem surprising that the same can be said for Theofanidis’s

Rainbow Body.

Unlike Copland, who drew on American folklore and the seemingly limitless possibilities of the American experiment, Theofanidis has drawn from the deep wells of Medieval chant and Buddhist philosophy for the raw materials of this concert opener.

“I have been listening a great deal to the music of the 12th-century German Benedictine abbess, writer, composer and mystic Hildegard von Bingen, and, as simple and direct as her music is, I am constantly amazed by its staying power,” says Theofanidis. “Hildegard’s melodies have memorable contours which set them apart from other chants of the period. They are very sensual and intimate, a kind of communication with the divine.

Rainbow Body

is based on one of her chants,

Ave Maria, O auctrix vite (‘Hail Mary, source of life’). “Rainbow Body begins in an understated, mysterious manner, calling attention to some of the key intervals and motives of the piece. When the primary melody enters for the first time about a minute into the work, I present it very directly in the strings without accompaniment. In the orchestration, I try to capture a halo around this melody, creating a ‘wet’ acoustic by emphasizing the lingering reverberations one might hear in an old cathedral.”

The specific technique Theofanidis uses for this effect is worth a bit of exploration. “He creates resonance,” notes Spano, “by having some instruments prolong a note after the tune has moved on to the next, and the next, and the next note.” The result is a unique acoustic experience achievable only with a symphony orchestra.

The title,

Rainbow Body, comes from the Tibetan Buddhist concept of enlightenment, wherein a dead body is absorbed as light and energy back into the universe, at which point it is known as a “rainbow body”, meaning there is no decay or atrophy of any existing substance, merely a recycling of positive energy.

It was positive energy too, and of a distinctly American vein, that helped give birth to the final masterpiece on this program: Dvořák’s exquisite Cello Concerto.

When he came to the US in 1891 to become the head of the American Conservatory of Music in New York, Antonín Dvořák’s patron, Mrs. Jeannet Thurber, intended him to be the founder of not only the first conservatory in the US but also the founder of a national musical identity. It was this outsider from Bohemia that made American composers stop looking toward Europe for inspiration and look closer to home, at the negro spirituals and other native music sources that were to form the inspiration for so much American music in the 20th century.

Within a year of his appointment to this post, Dvořák began writing four new works: Symphony in E-Minor (From the New World,) his “American” String Quartet No. 12, the fantastic String Quintet No. 3, Op. 97, and lastly his Cello Concerto.

Initially, Dvořák wasn’t entirely keen on the idea of the cello as a solo instrument. “The cello is a beautiful instrument,” he wrote, “but its place is in the orchestra and in chamber music. As a solo instrument it isn’t much good because the upper voice squeals and the lower growls.”

This opinion notwithstanding, Dvořák’s friend and colleague cellist Hanuš Wihan had long pleaded for a concerto to be written for him. But it took a pair of essentially American experiences for the Bohemian to start seeing the potential of such an endeavor.

The first was a concert in Brooklyn, where Dvořák heard a cello concerto by Victor Herbert (best known today for the operetta

Babes in Toyland), that opened his eyes and ears to ways of navigating some of the technical challenges to writing a cello concerto. The second was a visit to Niagara Falls, which engaged the rest of his senses and reportedly inspired Dvořák to exclaim out loud, “My word, that is going to be a symphony in B minor!” Though he never ended up writing a symphony in B minor, his resulting Cello Concerto in B minor is certainly symphonic in scope.

Dvořák began work on the concerto in the spring of 1894, while on a brief visit home to Bohemia, completing it in February the following year when back in New York. While composing the concerto, he received a letter that his sister-in-law, Josefina Čermáková, was dying. Before Dvořák married her sister, Anna, he had been hopelessly in love with Josefina, but this love was unrequited. They had stayed close friends, however, and he was devastated upon receiving the letter. In an act of dedication, he quotes Josefina’s favorite song of his, “Lass mich allein in meinen Träumen geh’n” (“Leave me to walk alone in my dreams”), in the

Adagio

second movement. The

Adagio

also contains a discreet funeral march with a triplet figure in the horns under the

cantabile

theme. The contemplative mood of the ending, too, is in reverence to her memory. One month after Dvořák returned home, Josefina died.

But despite the sad circumstances surrounding much of its creation (or perhaps owing to the depth of the emotions experienced during that time), the premiere of the work in London in 1896, with the composer at the podium, was a huge success. Much like Dvořák’s experience with the Herbert concerto in Brooklyn, Johannes Brahms himself (not usually one to give high praise to other composers), was genuinely impressed; writing in a congratulatory letter to Dvořák, “How could I not have known that one can write a cello concerto like this? If I had known, I would have written one long ago!”

Program Notes by Jamie Allen © 2025 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Recommended Recordings:

Yo-Yo Ma has made two recordings of the Dvořák Cello Concerto. Lorin Maazel conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in his first, released in 1986. Kurt Masur conducted the New York Philharmonic in the 1995 recording, which also features the rarely heard Second Cello Concerto of Victor Herbert, thus pairing two cello concertos composed in America. Both recordings are on Sony Classical, and both communicate the joy in Yo-Yo Ma's performance heard at this concert.

Rainbow Body by Christopher Theofanidis and Appalachian Spring by Copland have both been recorded by Robert Spano with the Atlanta Symphony and are coupled together on the same disc released by Telarc.

Only a few seats remain! Click HERE or call 401-248-7000 to purchase today!