THE STORY BEHIND: Strauss' "Also sprach Zarathustra"

Share

On October 15, Tania Miller and the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra will present STERLING ELLIOTT with cellist Sterling Elliott.

THE STORY BEHIND: Strauss'

Also sprach Zarathustra

Title: Also sprach Zarathustra, op.30, TrV 176

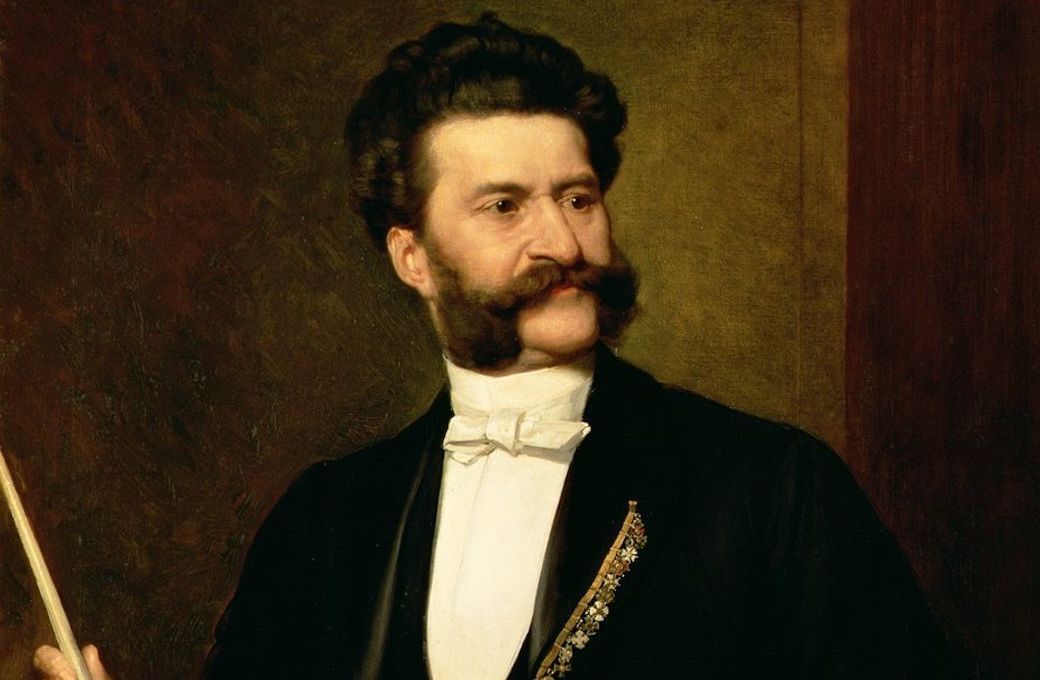

Composer: Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic: Last performed February 26, 2011 with Larry Rachleff conducting. This piece is scored for three flutes, piccolo, three oboes, English horn, two clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, three bassoons, contrabassoon, six horns, four trumpets, three trombones, two tubas, timpani, percussion, two harps, organ and strings.

The Story:

Hardly was the ink dry on the score of Richard Strauss’s

Till Eulenspiegel in 1895, when he began to sketch a new symphonic poem.

Till

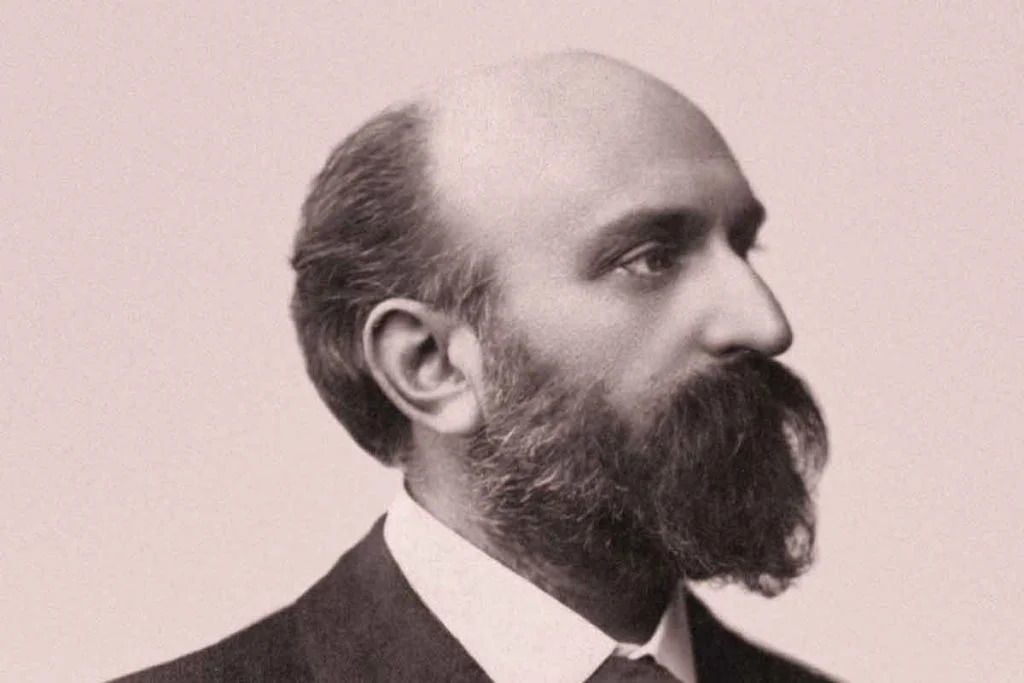

had been one of Strauss’s most pictorial, illustrative works for orchestra, but the new piece would be inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophical writings. Young Germans of Strauss’s generation had avidly read Nietzsche’s poetic-philosophical book,

Thus Spoke Zarathustra. The book’s hero, named after the pre- Christian Persian prophet, seemed to exemplify the fin-de-siècle artistic ideals of the time: a “super-person” who is a free spirit longing after higher aspirations than his world seems to offer.

It came as no surprise that when Richard Strauss announced the subject of his new symphonic poem, a great outcry went up. Philosophy through music? Ridiculous! Yet, unknown to Strauss or anyone else, Nietzsche had confided to his journal that the nature of

Zarathustra

belongs “almost among the symphonies.” On the eve of

Zarathustra’s

premiere in December 1896, Strauss felt it necessary to clarify his position and wrote:

I did not intend to write philosophical music or portray Nietzsche’s great work musically. I meant rather to convey in music an idea of the evolution of the human race from its origin, through the various phases of development, religious as well as scientific, up to Nietzsche’s idea of the Übermensch [super-person].

As Strauss suggested, the relationship of his work to Nietzsche’s is very general. Of Nietzsche’s 80 chapter headings, Strauss chose only eight for his score, and they come in an order unrelated to Nietzsche’s book.

The famous (2001: A Space Odyssey) introductory depiction of dawn has no subheading. Instead, Strauss reprints

Zarathustra’s

preface, which begins:

When Zarathustra was 30 years old, forsaking his home and the lake by his birthplace, he took to the mountains. There he enjoyed his loneliness, communing with his soul, and did not tire of this for ten years. But at last a change was wrought in his heart, and one morning he arose with the dawn and turned to the sun. . . .

The key of the opening is C, symbolizing the purity and simplicity of Nature. In sharp contrast to this, the first section, “Of the Otherworldsmen,” introduces the key of B (minor and later major), which represents Humankind. This key relationship is symbolically paradoxical, since B is next to C but is very distantly related to it in sound.

The ascending Nature motive from the introduction becomes transformed many times in the course of

Zarathustra, but initially it occurs in the second section, “Of the Great Yearning.” The two nervously twisting themes in “Of Joys and Passions” combine in “The Dirge.” In the next section, “Of Science,” Strauss symbolizes learnedness by a fugue with a theme based on

Zarathustra’s

opening theme. The complex emotional content of “The Convalescent” gains relief in the rhythms of “The Dance Song” with its mocking suggestion of the super-person dancing a cabaret waltz. The final section, “Night-Wanderer’s Song,” opens with the tolling of midnight bells. A mood of hushed mystery prevails over the closing pages of the score. In the final measures comes a quiet, subtle return of the original struggle between the tonalities B (Humankind) and C (Nature). “At the end,” remarks Strauss scholar Norman Del Mar, “for all Man’s achievements and hard-won peace of mind, Nature inevitably has the last word, as Nature always will, whatever beings Earth may conjure up to dispute her sovereignty.”

Program Notes by Dr. Michael Fink © 2022 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Tickets start at $15! Click HERE or call 401-248-7000 to purchase today!