THE STORY BEHIND: Saint-Saens’ Cello Concerto No.1

Share

THE STORY BEHIND: Saint-Saens’ Cello Concerto No.1

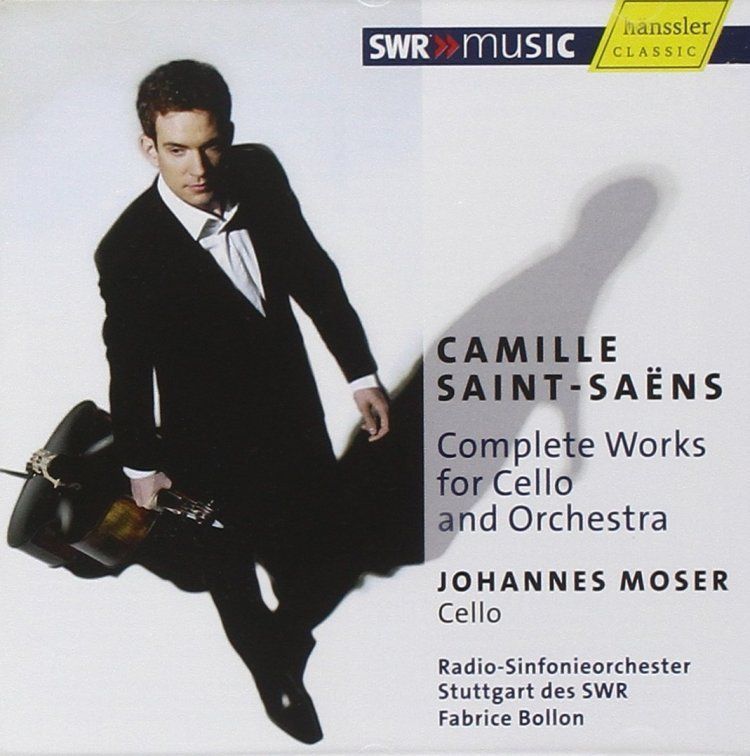

On February 14 & 15, cellist Johannes Moser will join Tania Miller, the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra for a romantic Valentine’s Weekend program.

THE STORY BEHIND: Saint-Saens’ Cello Concerto No.1

Title: Cello Concerto No.1 in A Minor, Op.33

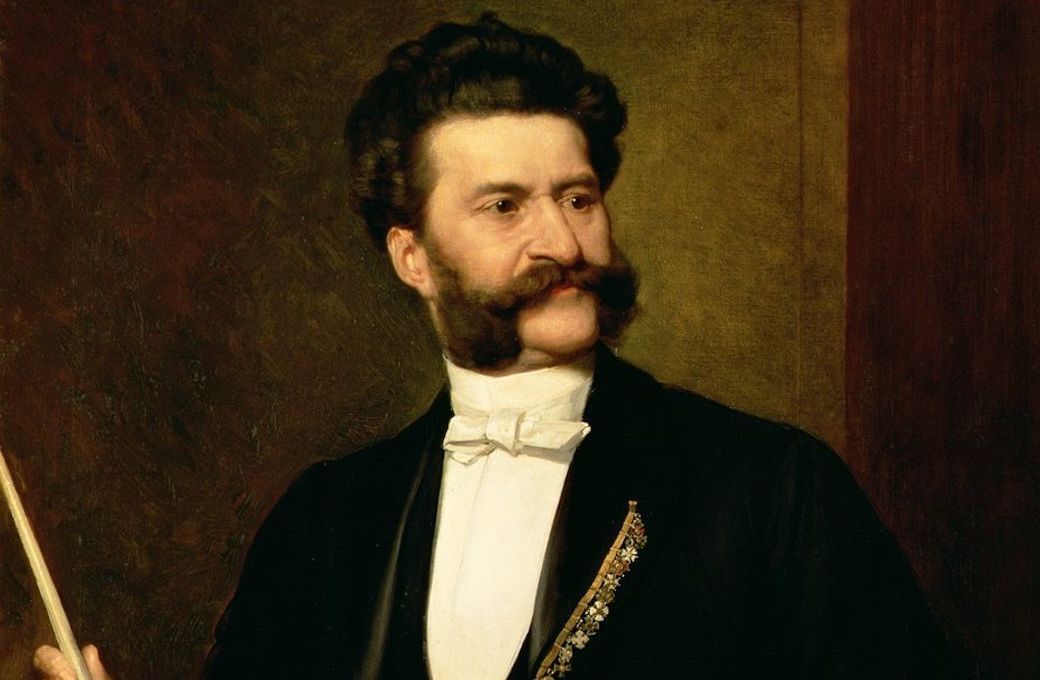

Composer: Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic: April 11, 2015 with soloist Alban Gerhardt

Orchestration: In addition to a solo cello, the work is scored for two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets, timpani and strings.

The Story:

At age 37, Camille Saint-Saëns was a productive, crusading composer. He was determined to resuscitate the true spirit of French music, which he viewed as having become stagnant and sterile under the heavy influence of Wagner. Not that Saint-Saëns was entirely anti-German. In fact, that year (1872) under the pen name of Phémius, he began writing music criticism favoring Germanic composers Handel and Liszt alongside his particular French favorites, Rameau and Gounod. His own music also showed strong traces of the German symphonic school, since there was no real French symphonic tradition at the time.

One of Saint-Saëns’s most concise yet most important contributions to the symphonic idiom is his Cello Concerto in A Minor, written the same year he took up the pen as Phémius. It is a work that makes effective, occasionally showy, use of the solo cello without ever degrading the part with empty virtuosity. It is a tightly knit work as well, written in three compact movements that connect without pause. The music has a thematic economy: The first movement’s main theme returns prominently in the finale and then is transformed into a new theme. Continuous form, thematic recursion and transformation—these are Lisztian techniques that Saint-Saëns adapts expertly.

The first movement immediately introduces the main theme, a melody of flaring arabesques that shows off the cello well. A second, sustained theme contrasts sharply, and both themes play important roles in the movement’s working-out.

The middle movement is an Allegretto in minuet rhythms. Scored chiefly for muted strings, the movement allows the solo cello to outline the dance in delicate gestures. In place of a Trio section, the composer gives the cello a short, restrained solo cadenza (the only one in the concerto). A reprise of the minuet follows, but more vividly colored and more romantic.

Creeping in quietly, the original main theme announces the opening of the finale. A gradual dynamic build leads to the cello’s entrance on the theme, which is rhapsodically spun out, leading soon to a second theme. This, however, is a subtle transformation of elements from the minuet theme and the main theme. The rise and fall shape of the minuet theme joins the twisting motion and triplet rhythms of the main theme to generate a new idea. Later in the movement, just before the restatement, the cello plays a particularly effective high scale. A full, quick-tempo coda in a major key gives the cello some brilliant scale passages and rounds out the work. Musicologist/conductor Donald Tovey summed up this concerto with the remark that it is “pure and brilliant without putting on chastity as a garment, and without calling attention to its jewelry at a banquet of poor relations.”

Program Notes by Dr. Michael Fink © 2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED