THE STORY BEHIND: Ravel's Piano Concerto in G major

Share

On November 13, Kensho Watanabe and the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra will present Romantic Rachmaninoff with pianist Natasha Paremski.

THE STORY BEHIND: Ravel's Piano Concerto in G major

Title: Piano Concerto in G major

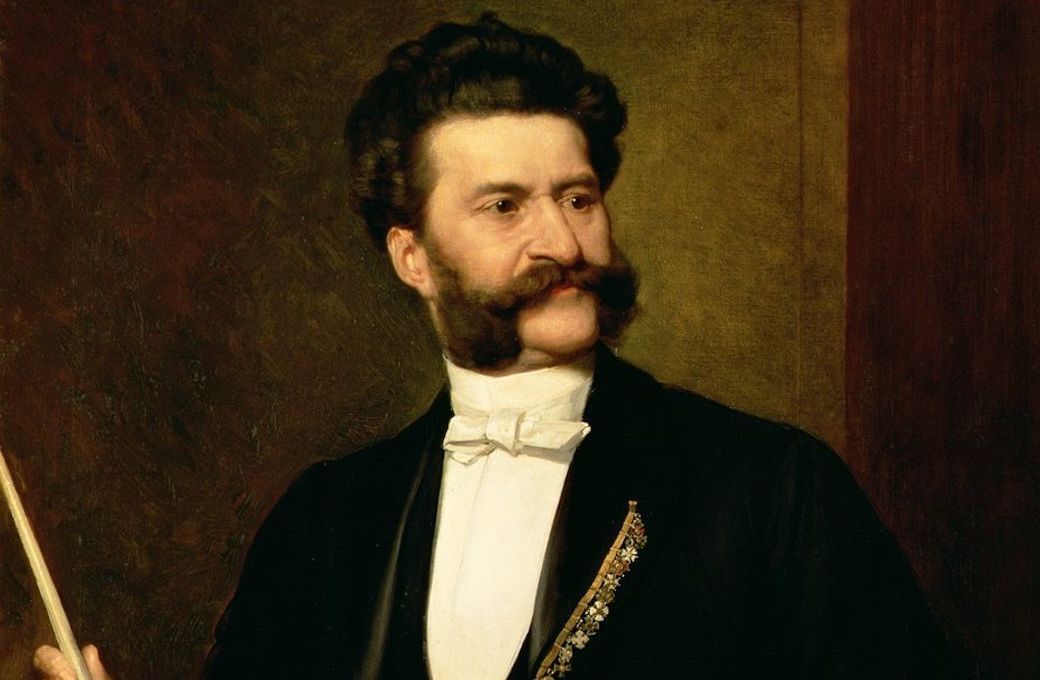

Composer: Maurice Ravel

(1875-1937)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic: Last performed October 15, 2011 with Michael Stern conducting and soloist Joyce Yang. In addition to a solo piano, this piece is scored for flute, piccolo, oboe, English horn, clarinet, E-flat clarinet, two bassoons, two horns, trumpet, trombone, timpani, percussion, harp and strings.

The Story:

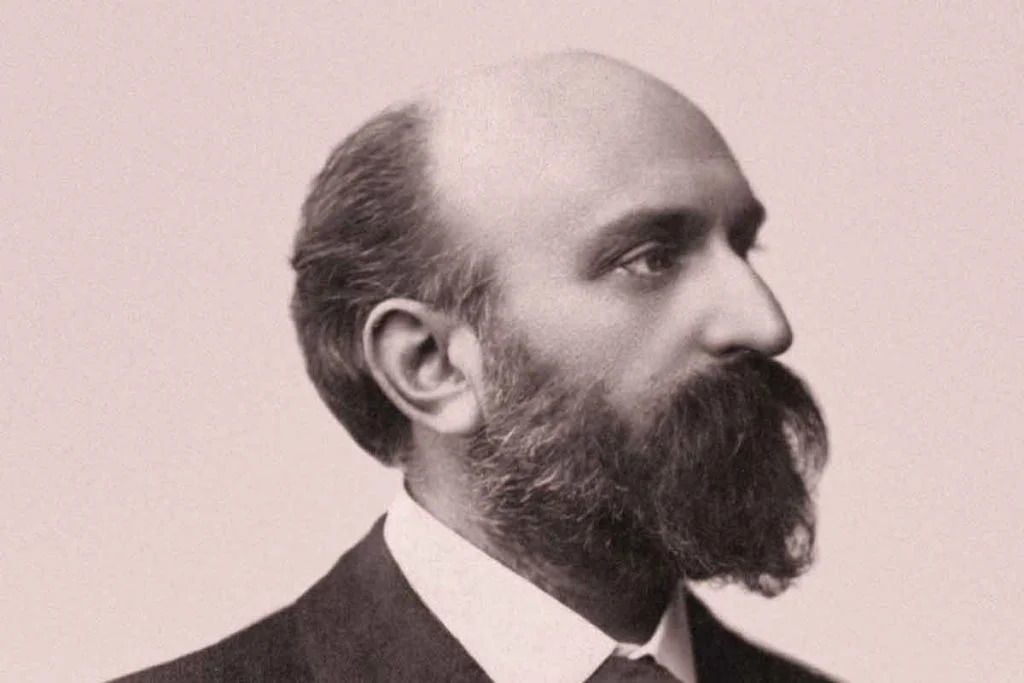

An apocryphal anecdote relates that when George Gershwin asked Maurice Ravel to give him composition lessons, Ravel asked Gershwin how much money he was earning from music. On hearing some astonishing figure, Ravel supposedly responded, “Perhaps, I should take lessons from

you!” The meeting actually took place, but Ravel really said, “You would only lose the spontaneous quality of your melody and end by writing bad Ravel.”

In a way, Ravel did take lessons from Gershwin. Several of Ravel’s works, notably his Piano Concerto in G Major, make use of jazz rhythms, “blue” notes, and other features of American vernacular style. The first movement of Ravel’s concerto (composed in 1931) is in several respects a remarkable sequel to Gershwin’s

Rhapsody in Blue (1924) and Concerto in F Major (1925). The frenetic rhythm patterns and Ravel’s “bluesy” main theme in this movement bear an uncanny resemblance to Gershwin’s adaptations of the jazz idiom.

The slow movement of the Concerto in G Major was, compositionally, one of the most difficult pieces Ravel ever wrote. He later remarked that he composed it two measures at a time, using as his inspiration Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet (K. 581). However, with its languid waltz rhythms and wandering melody, it also owes something also to Satie’s

Gymnopédies and Chopin’s Nocturnes.

The American jazz idiom returns in the finale, but in a subtler, more organic way than in the first movement. This lighthearted conclusion, in the words of Edward Downes, “flies at such supersonic speed that it seems to finish before it has started.”

The witty, playful nature of the outer movements reveals Ravel’s original intention to call the concerto a

Divertissement. This helps to explain the scarcity of blend between piano and orchestra. As Ravel himself commented:

A concerto can be gay and brilliant and need not try to be profound or strive after dramatic effects. It has been said of some of the great classic composers that their concertos were written, not for but against the piano, and I think this is perfectly correct.

Program Notes by Dr. Michael Fink © 2021 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Tickets start at $15! Click HERE or call 401-248-7000 to purchase today!