THE STORY BEHIND: Brahms' Violin Concerto

Share

On January 22, Bramwell Tovey and the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra will present Beethoven 5 with violinist Benjamin Beilman.

THE STORY BEHIND: Brahms 'Violin Concerto

Title: Violin Concerto, op.77, D major

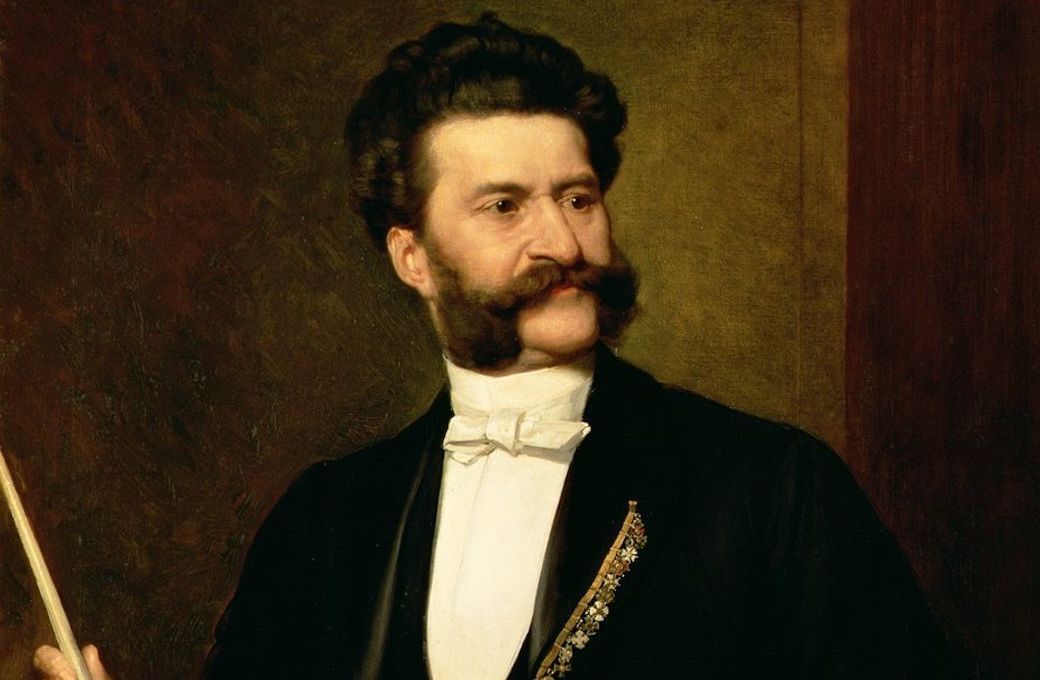

Composer: Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic: Last performed January 24, 2009 with Larry Rachleff conducting and soloist Jennifer Koh. In addition to a solo violin, this piece is scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, timpani and strings.

The Story:

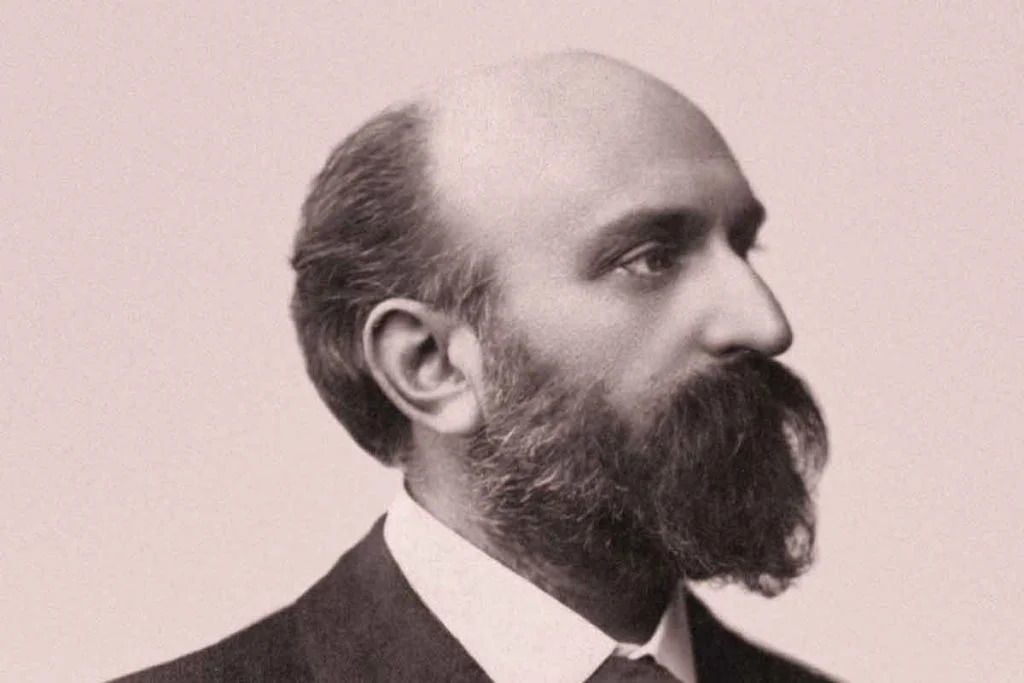

“You will think twice before you ask me for another concerto!” wrote Johannes Brahms to violinist Joseph Joachim, his lifelong friend and advisor on violinistic matters. The year was 1879, and on that New Year’s Day, Joachim had just premiered Brahms’s Violin Concerto in Leipzig. The reception had not been very gratifying, partially because the violin part sounded unduly difficult and labored. That was the view of conductor Hans von Bülow, who stated that the concerto was written “against the violin.” (Violin prodigy Bronislav Hubermann later countered with the remark that it is a concerto “for violin against orchestra — and the violin wins.”)

As usual, Brahms had modeled the proportions — and something of the approach to solo violin treatment — on a parallel work by his transcendental idol, Beethoven. In its day, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto had also been accused of unwarranted difficulties, and early audiences often missed its profound content. Brahms placed his concerto in the key of D major, the key of Beethoven’s great work.

D major also happens also to be the key of Brahms’s Second Symphony, finished less than a year ahead of the concerto. The Violin Concerto is a companion piece to the symphony in other ways, too, notably the use of a broken chord as the basis of the opening theme. This theme in the concerto is the focus of the orchestra’s brief opening. At the entry of the violin, this theme returns but eventually gives way to others, including a gloriously sweet, song-like second theme. Following Classical tradition, Brahms leaves the long solo passage near the end of the movement (the “cadenza”) up to the performer (as Beethoven, another non-violin-soloist, had done). This concerto is virtually the last one to do so, granting an opportunity for virtuosos from Joachim to Perlman to make their own mark on Brahms’s first movement.

Brahms had originally intended two middle movements. However, he discarded them, placing there instead what he modestly called “a feeble Adagio.” Far from feeble, this is some of Brahms’s richest writing for orchestra, exploring remote keys and supporting a lovely, decorative violin line.

The finale is a Hungarian-style piece. It has a rhythmically athletic main theme and contrasting episodes (also with soloistic acrobatics) to charm the listener. Near the end, the short cadenza by the composer leads to a concluding section that first builds excitement and then, as in a Mozart opera, subsides into restrained propriety for its grand ending.

Brahms’s Violin Concerto stands as a great musical pillar near the end of the 19th century, counter-balancing the pillar of Beethoven’s great Violin Concerto from the beginning of that century. As analyst John Horton has put it:

"That Brahms should have ventured upon a Violin Concerto in D with the sound of Beethoven’s . . . in his ears was in itself an act of faith and courage; that he should have produced one . . . worthy to stand beside it, is one of the triumphs of Brahms’s genius."

Program Notes by Dr. Michael Fink © 2021 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Tickets start at $15! Click HERE or call 401-248-7000 to purchase today!