THE STORY BEHIND: Beethoven's Symphony No.9 (Choral)

Share

On May 7, Leonard Slatkin, Providence Singers, Talise Trevigne, Nina Yoshida Nelsen, Colin Ainsworth, Michael Dean and the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra will present Beethoven 9.

THE STORY BEHIND: Beethoven's Symphony No.9 (Choral)

Title:

Symphony No.9, op.125, D minor (Choral)

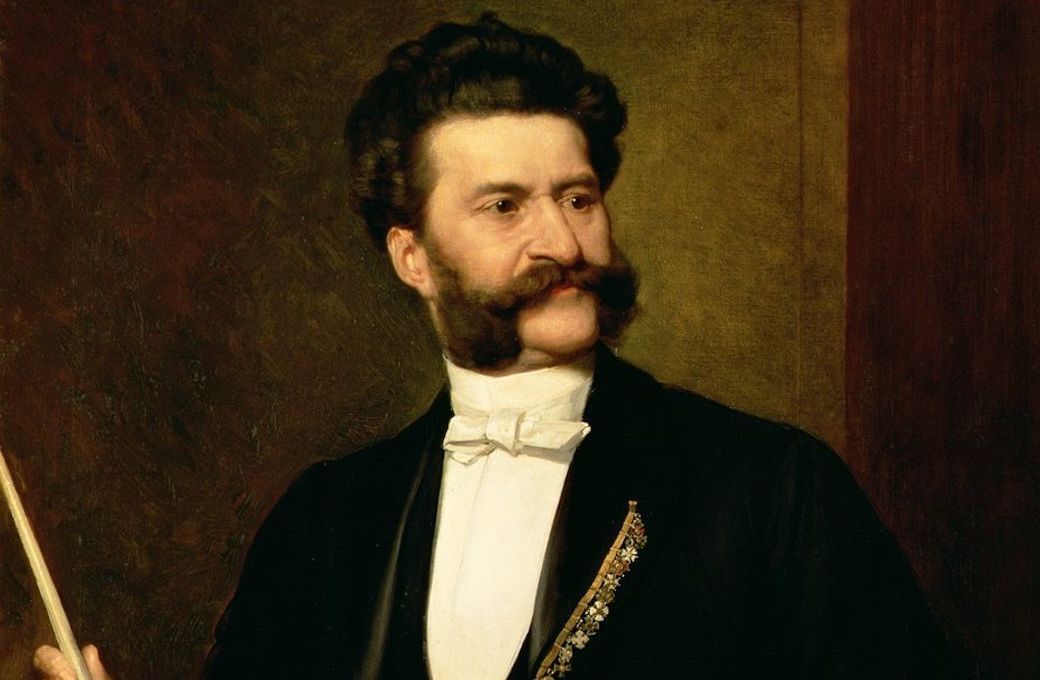

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

(1770-1827)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic:

Last performed May 10, 2010 with Larry Rachleff conducting, Providence Singers, and soloists Michelle Areyzaga, Susan Lorette Dunn, Aaron Blake and Robert Honeysucker. In addition to a chorus, a solo soprano, alto, tenor and bass, this piece is scored for two flutes, piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, percussion and strings.

The Story:

The history of the composition of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is among the longest and most interesting of any of his compositions. As early as 1793, Ludwig van Beethoven conceived the idea of setting Friedrich Schiller’s

Ode to Joy but did nothing about it. Nearly 20 years later, he made a note among sketches for an “overture” that read, “disjointed fragments from Schiller’s

Freude

[joy] connected into a whole.” But as yet, there were no musical connections. The Scherzo’s main theme became the first, appearing in a notebook of 1815, although at the time Beethoven was sketching the Cello Sonata, Op. 102. In 1817, he became serious about composing a new symphony, and he sketched the beginning of the Ninth’s first movement. However, the composer did no more until 1822, when he again addressed the first movement and set down plans for the second and fourth movements, including the beginning of the famous

Ode to Joy hymn theme. The following year, the symphony crystallized completely. Beethoven finished the sketch by the end of 1823 and completed its orchestration the following February. It had taken the composer more than six years to

complete

his final symphony, and the total gestation period had exceeded 30 years!

The story of the Ninth Symphony’s premiere is a famous one. Because of his deafness, it was impossible for Beethoven to conduct. Instead, Michael Umlauf assumed those honors at the first performance, which took place on May 7, 1824. Beethoven had supervised rehearsals, and during the performance, he was on stage, following it with a score in his own way. Some choral singers omitted the grueling high notes, and the large orchestra could not have performed adequately. Nonetheless, the audience response was resounding. Beethoven, engrossed in his score, did not notice that the performance had ended. A soloist had to nudge and turn him so that he could see the audience applauding and waving handkerchiefs.

What to listen for: The opening of the first movement has often been identified with the Biblical Creation. In this prologue, the quivering string sounds might suggest void and chaos. Notice how the full orchestra gradually gathers itself to make these sounds into an actual theme.

We do not know whether Beethoven meant to paint the Creation, but this is certainly his most arresting instrumental opening. If Beethoven implied the world’s beginning at the outset of the movement, the final measures may intimate its end. Annotator Edward Downes suggests that the ending “seems an apocalyptic vision.”

The fourfold “hammer strokes” at the opening of the Scherzo movement become the motto for what follows. Notice how this hammer-stroke rhythm persistently returns in all sorts of musical guises. In the middle of the movement, the motto runs headlong into the Presto Trio section. Here, refreshing changes in the music give us a break before a reprise of the main Scherzo. At the movement’s ending, notice the reminiscence of the Trio one last time.

“In the slow movement, Beethoven explores melody to its inmost depths,” writes analyst Donald Tovey about the Adagio. The composer presents two themes, which he alternately varies, decorates, and caresses. Try to identify the deeply reflective first theme and yearning second one. This is one of the most expressive slow movements in all of Beethoven’s music.

In the finale, Beethoven revolutionized the symphony by transcending its previous boundaries. Symphonies were supposed to be instrumental — no voices. By combining the instrumental and vocal media, Beethoven redefined what a symphony could be: a statement of deep feeling or philosophy expressed both verbally and musically.

The movement fuses vocal and instrumental music in several ways. Notice how the baritone soloist sings his text to the music you just heard the orchestra play after the crashing introductory passage. The main idea is the famous and very melodious Ode to Joy theme, Beethoven’s setting of the humanistic/spiritual poem by Schiller. The other vocalists contribute verses in which the music differs in some ways from the original Ode theme, but somehow they are all unified. Of special interest is the last, a heroic march for tenor and chorus in which Beethoven, for the first time in a symphony (ever), brings out the “Turkish” instruments, triangle, cymbals, and bass drum.

After the complex orchestral passage, listen for the grand choral reprise of the hymn theme. Then, notice how Beethoven continues to employ the chorus in a variety of moods and textures.

The concluding section has the feeling of a summing up. Beginning with the soloists and spreading to the chorus, excitement builds twice until it can no longer be contained. For each of those moments, Beethoven regroups at a slower tempo. The third build-up bursts into the long Prestissimo ending, emphasizing Beethoven’s personal “kiss for all the world.” Listen again for the “Turkish” percussion instruments. This time they add power to the symphony’s overwhelming final pages. Now, see if you agree with the words of Edward Downes: “Altogether, the finale is a structure of emotional depth and intensity, and musical splendor past description. The symphony ranks as one of the greatest achievements of the human spirit.”

Program Notes by Dr. Michael Fink © 2022 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Tickets start at $15! Click HERE or call 401-248-7000 to purchase today!