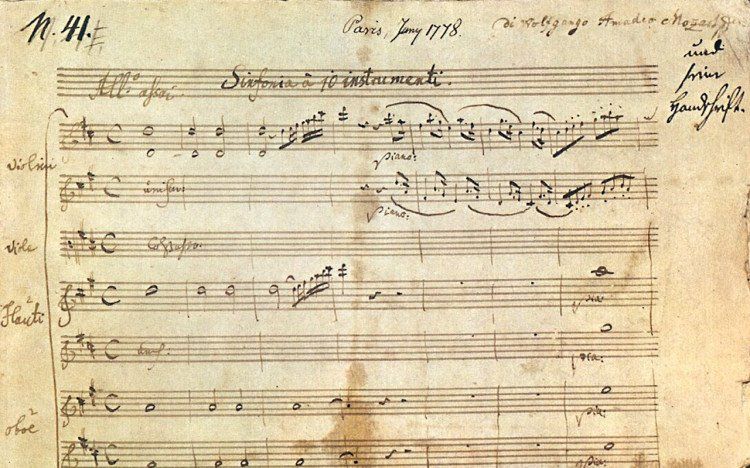

Dynamic contrast is the rhetoric of the Jupiter symphony’s opening two-motive theme, which Donald Tovey describes as “energetic gestures alternating with gentle pleadings.” The first movement’s second and concluding themes are lighter and more rococo. However, lightness is not long lived, as the latter becomes the theme of the development’s dramatic first half. In the second half, Mozart concentrates on the “energetic” first motive of the movement, leading naturally to a solid recapitulation.

In the Andante cantabile, also a sonata form, Mozart creates a mood by calling for muted strings. The idea of dynamic contrast recurs in this movement through sudden forte chords that punctuate the opening theme.

The serenity of the opening soon gives way to a mood of agitation and unrest that dominates much of the remainder of the movement. Only towards the end does the placid opening theme return.